In the presidential election of 1860, the Republican Party, led by Abraham Lincoln, had campaigned against the expansion of slavery beyond the states in which it already existed. The Republican victory in that election resulted in seven Southern states declaring their secession from the Union even before Lincoln took office on March 4, 1861. Both the outgoing and incoming U.S. administrations rejected secession, considering it rebellion.

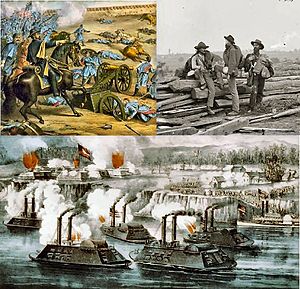

Hostilities began on April 12, 1861, when Confederate forces attacked a U.S. military installation at Fort Sumter in South Carolina. Lincoln responded by calling for a volunteer army from each state, leading to declarations of secession by four more Southern slave states. Both sides raised armies as the Union assumed control of the border states early in the war and established a naval blockade. In September 1862, Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation made ending slavery in the South a war goal, and dissuaded the British from intervening. Confederate commander Robert E. Lee won battles in the east, but in 1863 his northward advance was turned back at Gettysburg and, in the west, the Union gained control of the Mississippi River at the Battle of Vicksburg, thereby splitting the Confederacy. Long-term Union advantages in men and material were realized in 1864 when Ulysses S. Grant fought battles of attrition against Lee, while Union general William Sherman captured Atlanta, Georgia, and marched to the sea. Confederate resistance collapsed after Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865.

The American Civil War was the deadliest war in American history, causing 620,000 soldier deaths and an undetermined number of civilian casualties. Its legacy includes ending slavery in the United States, restoring the Union, and strengthening the role of the federal government. The social, political, economic and racial issues of the war decisively shaped the reconstruction era that lasted to 1877, and brought changes that helped make the country a united superpower.

The coexistence of a slave-owning South with an increasingly anti-slavery North made conflict likely, if not inevitable. Lincoln did not propose federal laws against slavery where it already existed, but he had, in his 1858 House Divided Speech, expressed a desire to "arrest the further spread of it, and place it where the public mind shall rest in the belief that it is in the course of ultimate extinction." Much of the political battle in the 1850s focused on the expansion of slavery into the newly created territories. All of the organized territories were likely to become free-soil states, which increased the Southern movement toward secession. Both North and South assumed that if slavery could not expand it would wither and die.

Southern fears of losing control of the federal government to antislavery forces, and Northern resentment of the influence that the Slave Power already wielded in government, brought the crisis to a head in the late 1850s. Sectional disagreements over the morality of slavery, the scope of democracy and the economic merits of free labor vs. slave plantations caused the Whig and "Know-Nothing" parties to collapse, and new ones to arise (the Free Soil Party in 1848, the Republicans in 1854, the Constitutional Union in 1860). In 1860, the last remaining national political party, the Democratic Party, split along sectional lines.

Both North and South were influenced by the ideas of Thomas Jefferson. Southerners emphasized, in connection with slavery, the states' rights ideas mentioned in Jefferson's Kentucky Resolutions. Northerners ranging from the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison to the moderate Republican leader Abraham Lincoln emphasized Jefferson's declaration that all men are created equal. Lincoln mentioned this proposition in his Gettysburg Address.

Confederate Vice President Alexander Stephens said that slavery was the chief cause of secession in his Cornerstone Speech shortly before the war. After Confederate defeat, Stephens became one of the most ardent defenders of the Lost Cause. There was a striking contrast between Stephens' post-war states' rights assertion that slavery did not cause secession and his pre-war Cornerstone Speech. Confederate President Jefferson Davis also switched from saying the war was caused by slavery to saying that states' rights was the cause. While Southerners often used states' rights arguments to defend slavery, sometimes roles were reversed, as when Southerners demanded national laws to defend their interests with the Gag Rule and the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850. On these issues, it was Northerners who wanted to defend the rights of their states.

Almost all of the inter-regional crises involved slavery, starting with debates on the three-fifths clause and a twenty year extension of the African slave trade in the Constitutional Convention of 1787. There was controversy over adding the slave state of Missouri to the Union that led to the Missouri Compromise of 1820, the Nullification Crisis over the Tariff of 1828 (although the tariff was low after 1846, and even the tariff issue was related to slavery), the gag rule that prevented discussion in Congress of petitions for ending slavery from 1835–1844, the acquisition of Texas as a slave state in 1845 and Manifest Destiny as an argument for gaining new territories where slavery would become an issue after the Mexican–American War (1846–1848), which resulted in the Compromise of 1850. The Wilmot Proviso was an attempt by Northern politicians to exclude slavery from the territories conquered from Mexico. The extremely popular antislavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852) by Harriet Beecher Stowe greatly increased Northern opposition to the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850.

The 1854 Ostend Manifesto was an unsuccessful Southern attempt to annex Cuba as a slave state. The Second Party System broke down after passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854, which replaced the Missouri Compromise ban on slavery with popular sovereignty, allowing the people of a territory to vote for or against slavery. The Bleeding Kansas controversy over the status of slavery in the Kansas Territory included massive vote fraud perpetrated by Missouri pro-slavery Border Ruffians. Vote fraud led pro-South Presidents Franklin Pierce and James Buchanan to make attempts (including support for the pro-slavery Lecompton Constitution) to admit Kansas as a slave state. Violence over the status of slavery in Kansas erupted with the Wakarusa War, the Sacking of Lawrence,the caning of Republican Charles Sumner by the Southerner Preston Brooks, the Pottawatomie Massacre,the Battle of Black Jack, the Battle of Osawatomie and the Marais des Cygnes massacre. The 1857 Supreme Court Dred Scott decision allowed slavery in the territories even where the majority opposed slavery, including Kansas. The Lincoln-Douglas debates of 1858 included Northern Democratic leader Stephen A. Douglas' Freeport Doctrine. This doctrine was an argument for thwarting the Dred Scott decision which, along with Douglas' defeat of the Lecompton Constitution, divided the Democratic Party between North and South. Northern abolitionist John Brown's raid at Harpers Ferry Armory was an attempt to incite slave insurrections in 1859. The North-South split in the Democratic Party in 1860 due to the Southern demand for a slave code for the territories completed polarization of the nation between North and South.

Other factors include sectionalism (caused by the growth of slavery in the lower South while slavery was gradually phased out in Northern states) and economic differences between North and South, although most modern historians disagree with the extreme economic determinism of historian Charles Beard and argue that Northern and Southern economies were largely complementary. There was the polarizing effect of slavery that split the largest religious denominations (the Methodist, Baptist and Presbyterian churches)

and controversy caused by the worst cruelties of slavery (whippings, mutilations and families split apart). The fact that seven immigrants out of eight settled in the North, plus the fact that twice as many whites left the South for the North as vice versa, contributed to the South's defensive-aggressive political behavior.

The election of Lincoln in 1860 was the final trigger for secession. Efforts at compromise, including the "Corwin Amendment" and the "Crittenden Compromise", failed.

Southern leaders feared that Lincoln would stop the expansion of slavery and put it on a course toward extinction. The slave states, which had already become a minority in the House of Representatives, were now facing a future as a perpetual minority in the Senate and Electoral College against an increasingly powerful North.

Support for secession was strongly correlated to the number of plantations in the region; states of the deep South which had the greatest concentration of plantations were the first to secede. The upper South slave states of Virginia, North Carolina, Arkansas, and Tennessee had fewer plantations and rejected secession until the Fort Sumter crisis forced them to choose sides. Border states had fewer plantations still and never seceded. As of 1850 the percentage of Southern whites living in families that owned slaves was 43 percent in the lower South, 36 percent in the upper South and 22 percent in the border states that fought mostly for the Union. 85 percent of slaveowners who owned 100 or more slaves lived in the lower South, as opposed to one percent in the border states. Ninety-five percent of blacks lived in the South, comprising one third of the population there as opposed to one percent of the population of the North. Consequently, fears of eventual emancipation were much greater in the South than in the North.

The Supreme Court decision of 1857 in Dred Scott v. Sandford added to the controversy. Chief Justice Roger B. Taney's decision said that slaves were "so far inferior that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect", and that slavery could spread into the territories. Lincoln warned that "the next Dred Scott decision" could threaten Northern states with slavery.

Abraham Lincoln said, "this question of Slavery was more important than any other; indeed, so much more important has it become that no other national question can even get a hearing just at present." The slavery issue was related to sectional competition for control of the territories, and the Southern demand for a slave code for the territories was the issue used by Southern politicians to split the Democratic Party in two, which all but guaranteed the election of Lincoln and secession. When secession was an issue, South Carolina planter and state Senator John Townsend said that "our enemies are about to take possession of the Government, that they intend to rule us according to the caprices of their fanatical theories, and according to the declared purposes of abolishing slavery." Similar opinions were expressed throughout the South in editorials, political speeches and declarations of reasons for secession. Even though Lincoln had no plans to outlaw slavery where it existed, Southerners throughout the South expressed fears for the future of slavery.

Southern concerns included not only economic loss but also fears of racial equality.The Texas Declaration of Causes for Secession said that the non-slave-holding states were "proclaiming the debasing doctrine of equality of all men, irrespective of race or color", and that the African race "were rightfully held and regarded as an inferior and dependent race". Alabama secessionist E. S. Dargan warned that whites and free blacks could not live together; if slaves were emancipated and remained in the South, "we ourselves would become the executioners of our own slaves. To this extent would the policy of our Northern enemies drive us; and thus would we not only be reduced to poverty, but what is still worse, we should be driven to crime, to the commission of sin."

Beginning in the 1830s, the U.S. Postmaster General refused to allow mail which carried abolition pamphlets to the South. Northern teachers suspected of any tinge of abolitionism were expelled from the South, and abolitionist literature was banned. Southerners rejected the denials of Republicans that they were abolitionists. The North felt threatened as well, for as Eric Foner concludes, "Northerners came to view slavery as the very antithesis of the good society, as well as a threat to their own fundamental values and interests."

Over the 1850s slaves left the border states through sale, manumission and escape, and border states also had more free blacks and European immigrants than the lower South, which increased Southern fears that slavery was threatened with rapid extinction in this area. Such fears greatly increased Southern efforts to make Kansas a slave state. By 1860 the number of white border state families owning slaves plunged to only 16 percent of the total. Slaves sold to lower South states were owned by a smaller number of wealthy slave owners as the price of slaves increased.

Even though Lincoln agreed to the Corwin Amendment, which would have protected slavery in existing states, secessionists claimed that such guarantees were meaningless. In addition to the loss of Kansas to free soil Northerners, secessionists feared that the loss of slaves in the border states would lead to emancipation, and that upper South slave states might be the next dominoes to fall. They feared that Republicans would use patronage to incite slaves and antislavery Southern whites such as Hinton Rowan Helper. Then slavery in the lower South, like a "scorpion encircled by fire, would sting itself to death." A few secessionists mentioned the tariff issue in addition to slavery, but these were rare. Among other reasons, slavery represented much more money than the tariff. However, a few libertarian economists place more importance on the tariff issue.

Non-slavery related causes of secession do exist, but have little to do with tariffs or states' rights.